Our time at the Allan Hills has come to an end

It has been three weeks since our last newsletter, and as I write to you nearly every member of our 2025-2026 field team has left our field camp at the Allan Hills after a very successful field season! So how did it end? Read on to catch up on our last two weeks in the field—weeks that tested our mettle, patience, and creativity while bringing the team even closer together right to the very end.

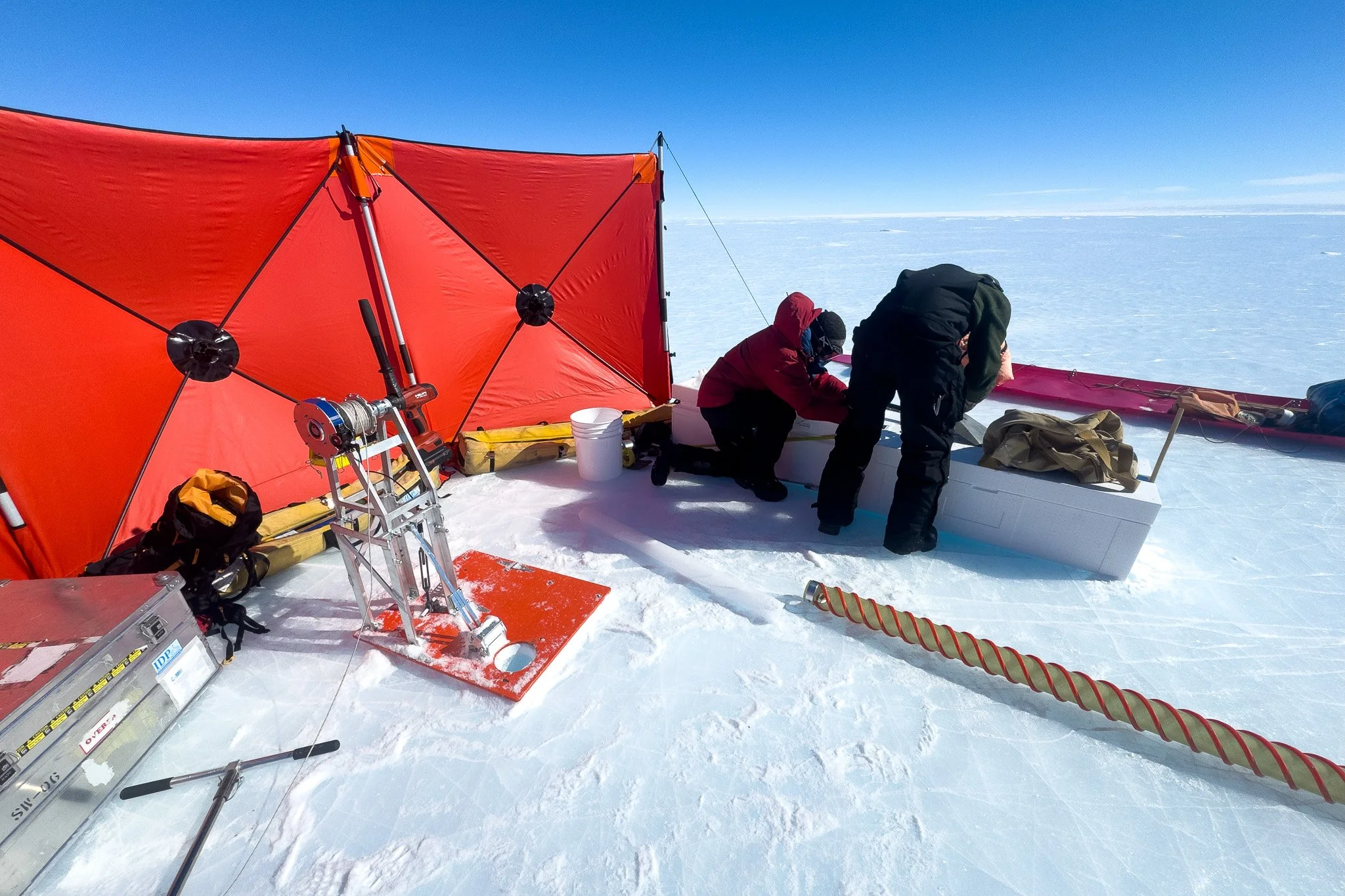

Our Allan Hills camp on a nice day.

In our last newsletter, written in the last few days of 2025, I shared how our team achieved our primary ice core drilling goals, reaching bedrock at our two main drill sites: 327 meters with the Shallow Wet Drill and 91 meters with our Blue Ice Drill. This in turn gave us the time to drill a new BID core of 26 meters, as well as collect a series of hand auger cores across our area of study and complete our geophysics goals.

Processing a core after hang augering it.

After a brief 2026 New Year’s celebration with the entire team, our countdown to departing the field and returning to McMurdo Station was on. With an out-of-camp date of January 10, 2026, we took inventory of all we had done and outlined all of our secondary and tertiary goals on a whiteboard as a team: more hand augers, more surface sampling, more geophysical surveys, and rock sampling. With just over a week to achieve all of these objectives, as well as pack up our thousands of pounds of science cargo and equipment, we dove into one final sprint at the Allan Hills.

With a lot to get done and weather being our only major obstacle, we dove in, tackling multiple projects at once. Precision GPS measurements of our BID boreholes took place while a team of two collected surface samples at the Cul-de-Sac. For those unfamiliar, surface sampling is a surveying method that allows us to get an estimate of the age of the ice in a specific area. We do this by collecting small amounts of surface ice from a specific area, each in their own bottle, collected in a straight line at various resolutions. We then measure the water isotopes in the samples, which can tell us how old the ice is by matching it to other measurements in the area. This information then helps our scientists determine where the old ice is, where it’s moving, and where we could possibly target to collect more old ice. We collected hundreds of surface sample bottles this season, each of which will be critical to helping us better understand this area!

Surface sampling in the Cul-de-Sac.

While geophysical equipment was being calibrated and the NSF Ice Drilling Program drillers with us packaged up their drilling equipment, a small hand augering team led by Oregon State University postdoc Ivo Strawson headed out onto the glacier to collect more ice cores. Snowmobiling to an area with visible tephra layers at the surface, we set up our trusty wind screen and, over the course of two days, hand drilled down to 20 meters, collecting a new ice core which included a section with a distinct dust band! This same team later collected another 17 meter hand auger core on a moraine in the Cul-de-Sac, bringing our total number of hand auger cores this season to four.

A dust band in one of our hand auger cores.

While more ice drilling was a big goal we were happy to meet, wrapping up our geophysical surveying of the area around us was also key to a successful field season. An Li, Geophysics Lead and PhD candidate at the University of Washington, led this effort, calibrating a Ground Penetrating Radar (GPR) and leading a team to drag across multiple areas around our camp. While we’ve used GPS (Global Positioning System) and ApRES (Autonomous phase-sensitive Radio Echo Sounder) this season to better understand vertical and horizontal glacier dynamics, GPR allows us to “see” into the ice all the way down to the bedrock thanks to radio waves. By dragging a sled with the GPR unit mounted on top over a glacier, we can view a live feed of the many features in the ice, like dust bands to rocks. Critical to successful ice core drilling, GPRing an area helps us get a very close estimate of how deep a glacier is, and how the glacier’s structure will affect future drilling in the area.

Our GPR sled. During normal operation, a person walks in the back while holding the live feed monitor.

Finally, on January 7, we reached a pivotal day of our field season: our last science day. Ending our science work a few days before our planned departure from the field allowed us to start an equally important part of being in the field: packing everything up. With thousands of pounds of scientific equipment, as well as samples, to organize, we took a half day to rest and assess. On the morning of January 8, science team members Danielle Whittaker, Romilly Harris Stuart, An Li, and I joined Polar Steam for a livestream from the field, answering questions submitted by teachers and students across the country. You can watch a recording of the livestream here.

Oregon State University postdoc Ivo Strawson operates the hand auger in the field.

With four flights to and from our field site scheduled that day, we left the livestream with a packed day ahead of us. First, a Twin Otter came to collect a penultimate shipment of ice core boxes. A Basler soon followed, picking up NSF IDP and camp cargo, and later that afternoon both planes returned, both collecting more cargo, equipment, and finally, our NSF IDP team members. After sweet goodbyes and see-you-laters, the drillers left, reducing our camp population to seven for the next couple of days.

The Basler plane that flew our NSF IDP colleagues and their cargo back to McMurdo Station.

With a lot of equipment left to organize, pack, and arrange on our cargo line for speedy loading on a plane, and only two days to do it, our work was cut out for us. In addition to scientific equipment clean up, we also had our sleep tents to deal with. Seven weeks of drifted snow had buried much of the bamboo and guylines around our tents, and the tedious but necessary labor of freeing the structures from the ice and snow was one more thing standing between us and being ready to fly back to McMurdo Station. A sprint ensued as we all raced to finish whatever it was that needed to be done, and on the morning of January 9, our planned flight date, ready to go, we woke up to… a weather delay. And a couple of hours later, a cancellation. Our next flight opportunity would be planned for the next day, as backups to other teams across the continent in the same situation as ours.

All, however, was not lost. More time in the field meant more time to tidy up even further, and time, after months of practically working non-stop, to rest a little bit. We spent the next four days in a state of pleasant limbo: reading in our hang out tent, watching a movie, journaling, chatting, walking around, taking photos. We took the opportunity to help our two Antarctic Support Contract staff organize camp as they took the lead in tearing it down. We cooked, we went on a hike, and, one our second to last day, snuck in some additional science work: a kite-powered aerial photo survey of the Cul-de-Sac! Finally, on the morning of January 14, our flight was activated, sending us into one final sprint as we took down two of our sleep tents (the other two staying to accommodate carpenters coming from McMurdo for camp take down), packed our bags one last time, and gathered by the airfield for our flight.

Some of our sleep kits and personal bags ready for loading onto our plane.

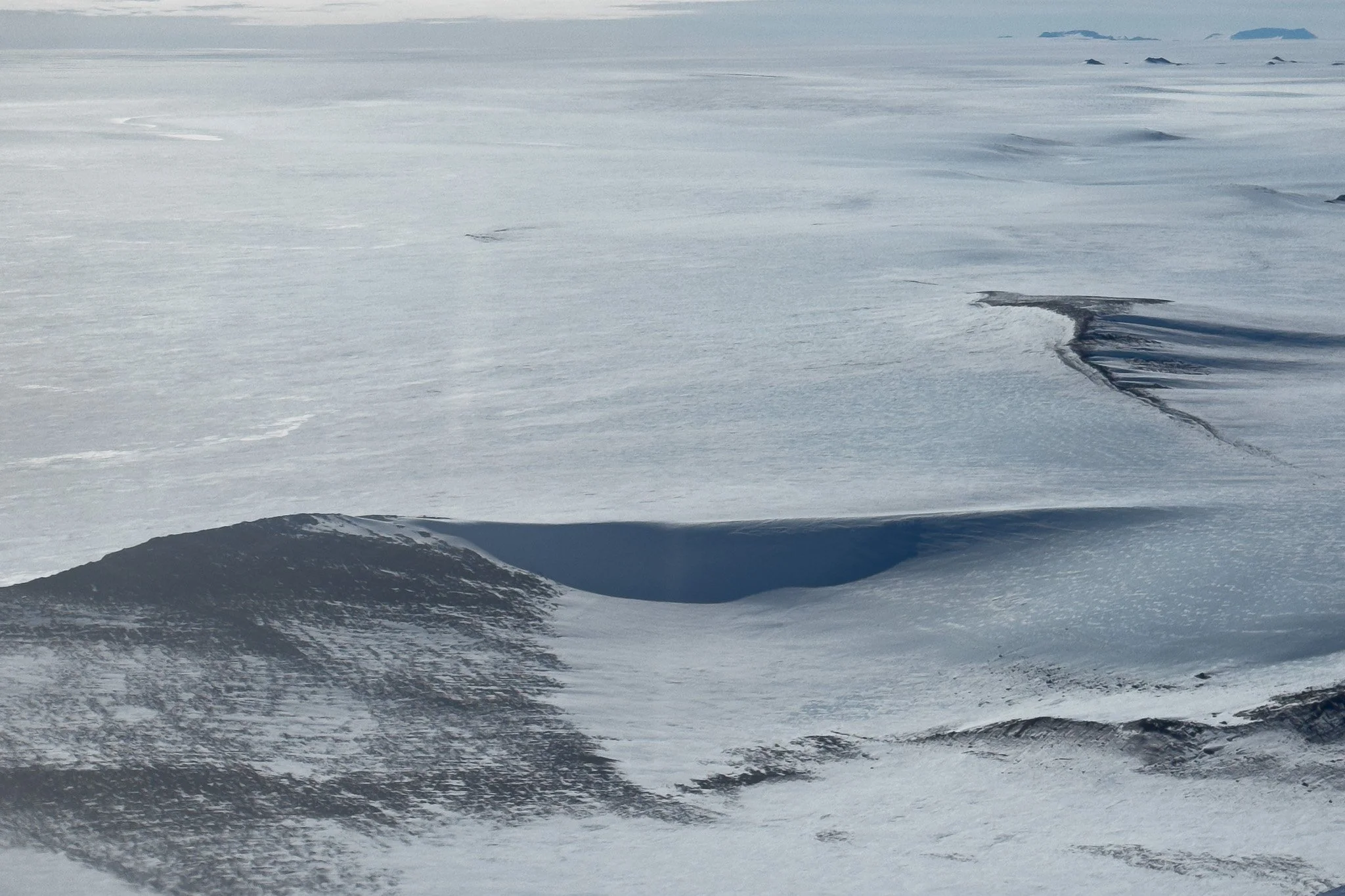

With cargo, bags, and passengers loaded, our Basler left the Allan Hills on time, gifting us with a beautiful view of camp, the Cul-de-Sac, and the Transantarctic mountains. Flying over the Ross Sea, we witnessed the sea ice breaking and icebergs floating off into the open ocean. Just over an hour later, we landed in McMurdo Station, 56 days after we left it. With more work ahead of us, we breathed a collective sigh—our equally wonderful and intense time in the field was over!

And that’s where I’ll stop for this long update. You can read all about what we did in McMurdo Station and a final recap of our entire field season in our next newsletter, which will come out in the next couple of weeks. Until then, thank you for following along these past few months and for supporting our work! As of this writing, our dedicated ASC staff are still at camp, living in one tent and sitting on 20,000 pounds of cargo which has yet to make its way back to McMurdo Station.

One last look at the Cul-de-Sac (foreground) and our camp (background, upper left) from our Basler as we flew back to McMurdo Station.

We’ll be back in your inbox soon!

~ Martin Froger Silva, NSF COLDEX Digital Content Coordinator and I-187M Ice Core Handler.

As a reminder, we’ve been updating you throughout the field season via our newsletter and this blog. We also post images, videos, and more on our Instagram and LinkedIn accounts, so follow us there if you haven’t done so already!

NSF COLDEX thanks the United States Antarctic Program for logistical support, with coordination and support from NSF Office of Polar Programs, NSF Antarctic Infrastructure and Logistics Program, the NSF Ice Drilling Program, the NSF Ice Core Facility, and the Antarctic Support Contractor.