NSF COLDEX field team celebrates the new year in Antarctica

Hello again from US National Science Foundation COLDEX, and happy new year to all! The end of 2024 marked a big milestone for our teams in Antarctica. Our I-187 team based at the Allan Hills, after weeks of touch-and-go weather conditions hampering their ability to drill for cores, was finally able to get down to consistently drilling in the last few weeks of December. Meanwhile, our I-186 team, based at South Pole Station and beyond, safely arrived at McMurdo Station after a weather-induced delay, and made a successful progression to South Pole Station. From there, they headed to ground “Site A”, about 400 kilometers from Pole up the flank of Dome A, where they have been successfully conducting geophysical surveys since. The team is supported by the Heavy Science Traverse, a US Antarctic Program tractor traverse platform that drove from McMurdo Station to South Pole and then Site A—itself quite an accomplishment!

Before the holidays, we received two updates from our field team: one from T.J. Fudge, Science Team Co-Leader for the I-187 Team and Research Associate Professor at the University of Washington, and one from Bridget Hall, Science Team member and Master’s student at the University of Minnesota.

First, T.J. Fudge’s update, written in December 2024:

“The weather has not been friendly, so we are still waiting to get our drill tents up and the ice coring going. We have been able to get out and do some glaciology and study how the ice moves.

Here’s Margot with a radar. You can see the controller, the yellow box, and one of the antennas to the right by the red flag. The other antenna is to the left, out of the picture.The antennas transmits energy and records the energy reflected from layers within the ice and from the rock beneath the ice. Ice is quite transparent to radar, so we can “see through” it and record the returned energy.

Image by T.J. Fudge.

Margot is making measurements where she can figure out how the ice crystals are oriented. And by making repeat measurements, she can see how the ice flows vertically. Here Margot is checking the radar settings. I promise she is not just trying to hide from me.

Image by T.J. Fudge.

Margot will make about 30 of these measurements throughout the region. She will then use them in an ice flow model to figure out how ice moves in the Allan Hills.

You know that wind is our main concern. It’s always windy here - that’s why there is old ice at the surface - but we have been hit with consistent high winds.

What you may not appreciate about camping in the wind is the noise. Not just the wind itself, but everything that it causes to flap. Here’s a video from inside my tent.

Video by T.J. Fudge.

The wind does make cool structures though.

Here is a feature I loved.

Image by T.J. Fudge.

One of the best parts about being a scientist is trying out new ideas. A few days ago, Margot and Liam set up a “tilted radar” experiment (Images by Margot Shaya and Liam Kirkpatrick):

They chiseled into the ice to set up the antennas at progressively larger angles. The reason is that the internal layers of the ice sheet and the bed of the ice sheet are tilted in this region. Liam measured an angle of about 20 degrees in the ice core, and previous radar measurements show the approximate slope of the bedrock.

The hope is that by orienting the radar at the same angle at the layers (i.e. making the radar wave propagation perpendicular to the layering), the reflected energy will create a stronger signal. Will it work? We have no idea. Lots of science is trying creative things that end up not working out.

The Allan Hills is a windy place. But occasionally, the storms align just right to produce snow and no wind. This happened the day I left the field. I zoomed with my son’s 5th grade class, and I couldn’t show them blue ice because there was a 1 inch thick layer of snow on the ground – and it hadn’t blown away!

The snow completely changed the landscape. The usually bare ice now looked like a more typical ice sheet. I think this combo of photos of our drill site is the best example. The first photo was taken from the ridge above, and you can just make out our drill tent in the middle of the ice slope. The second was taken from the airplane, and the ice is now covered by the thin layer of snow.

This snow only lasted about a day – before the wind and blowing snow returned.”

Image by T.J. Fudge.

And finally, in mid-December, T.J. sent us this very exciting update:

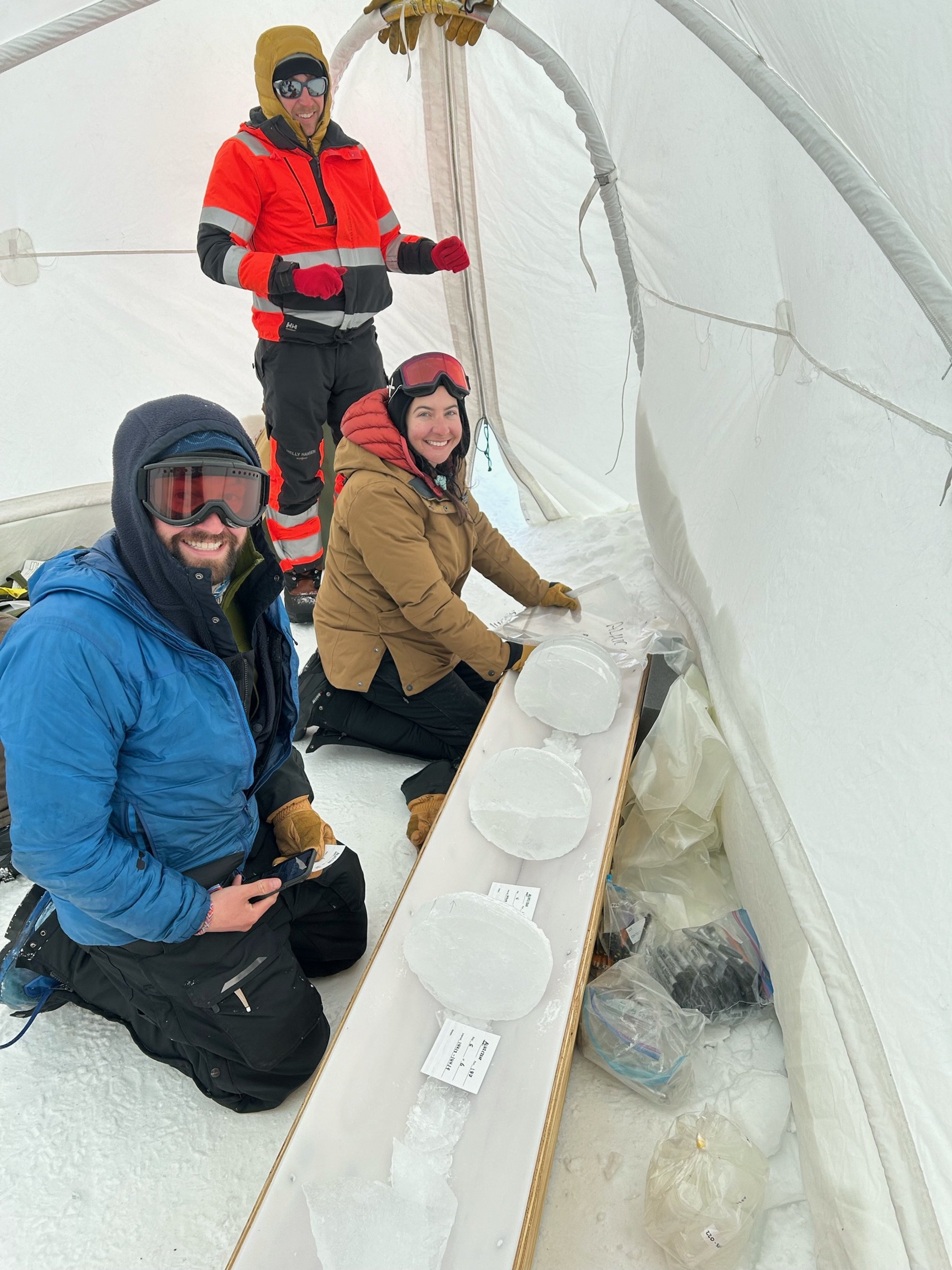

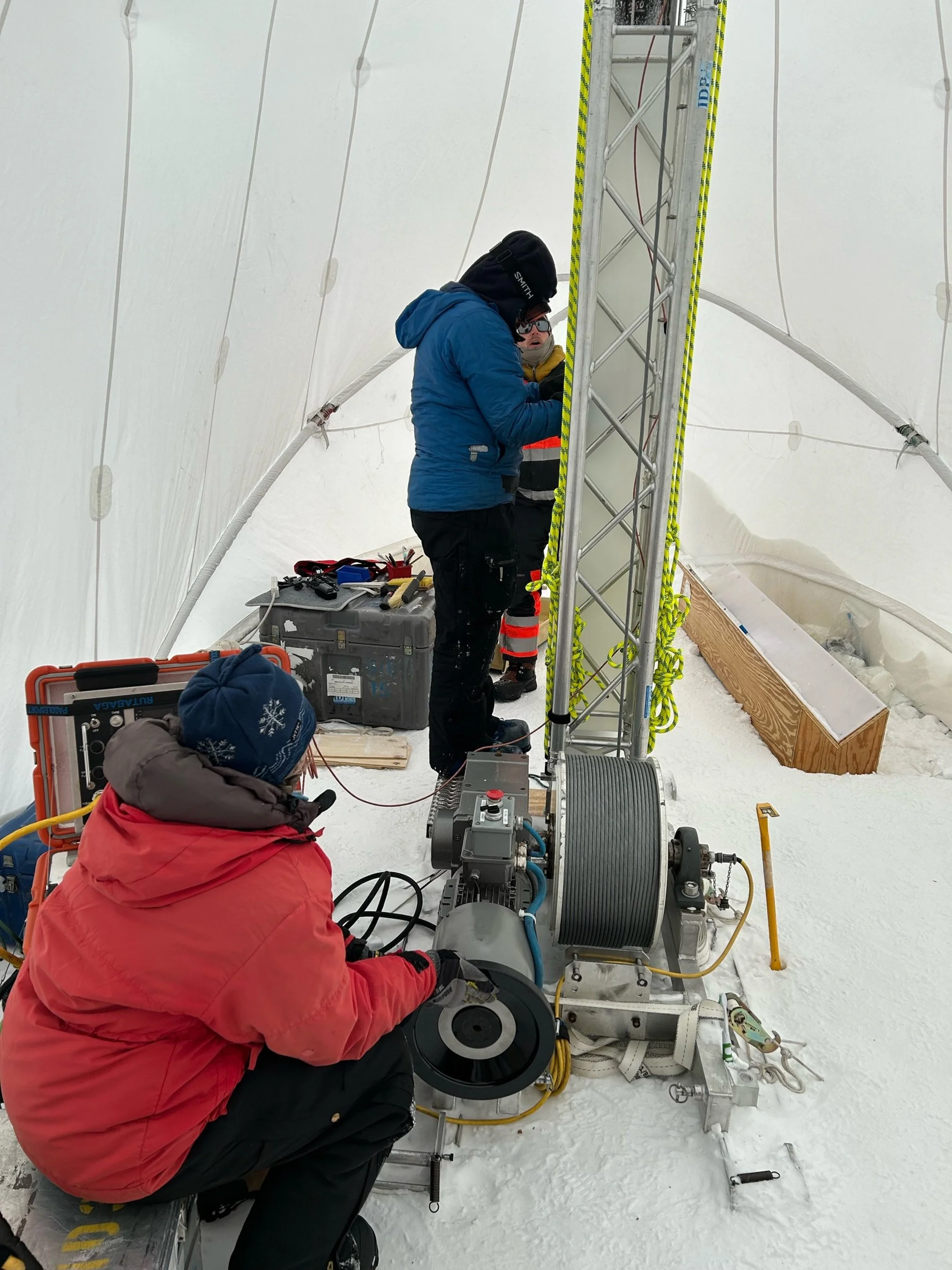

“It’s been quite a season getting camp and the main ice core drills up and running, but we have produced a core at last!

The NSF Ice Drilling Program “BID” – blue ice drill – has a diameter of 9.5 inches, compared to the drills I’ve used before which have a 4-inch diameter. Because we are *only* drilling to 200m, and not 2000m, we can recover much larger ice cores. These give us more ice to analyze since the layers are more compressed. The drill has a 2m long barrel that collects the ice core at the bottom, and the chips – the ice that gets cut out around the core. A good run at this depth brings up about 60 cm of ice.

The drilling of the ice core is a pretty slow process. First you lower the drill down, in this case about 150 m. Then we slowly lower it to the last meter so we don’t bang the drill on the ice. Then we start spinning the drill and cutting very slowly. The core quality is better with slower cutting, although getting good ice core quality is still very hard at Allan Hills.

Here’s an example of typical core quality. The alignment of pieces can be seen with the line drawn on the ice, but there are lots of cracks that run through the ice.”

Image by T.J. Fudge.

And that’s a wrap on T.J. Fudge’s coverage! Shortly after this last message, T.J. headed back home to the United States, and since then, the rest of the I-187 team has continued drilling and collecting cores, many of which are currently on their way back to McMurdo for storage and eventual transport to the NSF Ice Core Facility in Denver, Colorado.

Around the same time, Bridget Hall, science team member for the I-186 team, sent us the following update, with images taken by various members of the I-186 team:

“Our group is heading into the deep field from South Pole Station! Starting our travel from across the US, the team all converged in the Auckland Airport on November 29th to be split up again by cancelled flights to Christchurch. Little did we know this was foreshadowing for the next two weeks…

Our first couple days in Christchurch were spent as all teams spend them – trainings and a trip to the Clothing Distribution Center (CDC) to be issued our Extreme Cold Weather Gear (ECW). This is a long process of trying on clothing, switching out for other sizes and trying it on again until everything fits the way you want it to.

December 2nd was meant to be our first flight day, but early that morning we got the call that our flight was delayed 24 hours [because of the] weather. The next day we were delayed again, so when we got our flight confirmed on the 4th it was very exciting. We loaded onto the shuttles to head back to the CDC where we organized our stuff into the normal checked bags and carry-on bags, and then a third type of bag called a boomerang bag. The boomerang bag is a bag that you fill with things you would want in Christchurch in the unlikely event the plane had to turn around and land back in Christchurch rather than getting all the way to the ice. Basically, they don’t want to have to unload all of the checked luggage if that were to occur.

After 5 hours of crosswords, napping, and movies one of the flight crew got on the intercom to share the news - that unlikely event of a boomerang? It was happening…

Thumbs down for 5 more hours on the plane.

That’s when the cards came out, and the Early Career Researchers (ECRs) played multiple games of Euchre, which was a bit of a struggle for those of us that had never played as the loud plane made instructions very difficult.

Over the next 8 days each flight was delayed due to continuous bad weather, so we spent time exploring Christchurch. The ECRs also spent one day taking a trip out to Arthur’s Pass which featured massive limestone features and cool waterfalls.

On the 12th we had our lucky day, got onto the C130, and flew all the way onto the ice. The first evening in McMurdo was focused on becoming acquainted with the station – finding our rooms, enjoying a meal in the galley, and, for the ECRs, a tour around town.

Due to the flight delays, our time in McMurdo is significantly shorter than planned, and therefore getting all of our trainings in is a bit like playing Tetris. That being said, progress has been good: we’ve all been trained on snowmobiles, know how to spot signs of frostbite and hypothermia, and learned how to light whisper lite stoves. Incoming is the famous Deep Field Shakedown (DFS) where we will go through the process of setting up a camp and sleeping out a night to experience what the field site will be like, but in a more controlled environment.

There has been a lot of science prep as well! Many afternoons have been spent in this warehouse, collecting all our science cargo, putting things together to make sure they are all functional and everything needed is there. Eventually we will pack all the necessary equipment up as efficiently as possible for our flights to South Pole Station and our deep field site.”

JM working on the Distributed Acoustic Sensing system, John working on one of the six different radars, Ellen working on the ApRES (radar), and Knut and Megan working on the Magnetotelluric system.

NSF COLDEX team members are grateful for each and every community member at McMurdo Station. None of our science teams would succeed without the incredible skills and dedication of Antarctic Support Contract personnel!

Since we received this update, Bridget and the rest of the I-186 team has made it to South Pole Station, where they have been working extra long days to make up for lost time. We’ll share more about their progress in our next post, so stay tuned! As a reminder, we’re posting images, videos, and more on our newly created Instagram and LinkedIn accounts, so follow us there if you haven’t done so already.

NSF COLDEX thanks the United States Antarctic Program for logistical support, with coordination and support from NSF Office of Polar Programs, NSF Antarctic Infrastructure and Logistics Program, the NSF Ice Drilling Program, the NSF Ice Core Facility, and the Antarctic Support Contractor.